COLLECTIONS

Johannes Brahms: Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 2 in F Major, Op. 99 György Ligeti: Sonata for Solo Cello - Dialogo - Capriccio Dmitri Shostakovich: Sonata for Cello and Piano in D Minor, Op. 40

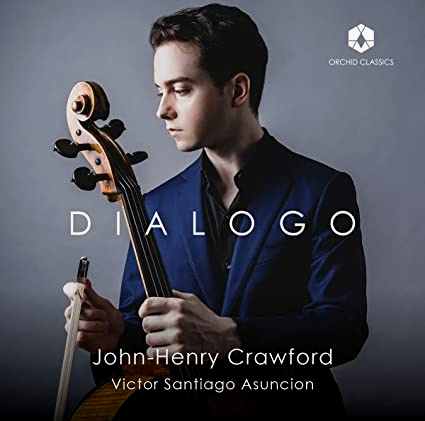

It's one thing to be hailed as a master cellist at such an early stage in one's career, and to have been the First Prize Winner of the IX International Carlos Prieto Cello Competition in 2019 and named Young Artist of the Year by the Classical Recording Foundation, but to present yourself to the world with an introductory recording with as varied and compelling a program as this one could very well be considered a feather in one's cap. American cellist John-Henry Crawford spans over 65 years of musical development in this overview of iconic works for the cello from Brahms to Ligeti.

As the Dialogo title of this CD implies, the Johannes Brahms Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 2 in F Major is very much a balanced dialogue between the two instruments in the form of a musical discourse structured around a sonata outline. The gist of the conversation is tossed around from cello to piano and back, with each one assuming the leading voice now and then, but it's the crosstalk between the two that forms the work's backbone, and generates its forward momentum. Crawford and pianist Victor Santiago Asuncion's fluid and at times animated playing certainly underlines the essence of the work.

As the booklet notes explain, the first movement "Dialogo" of the Sonata for Solo Cello by Hungarian composer György Ligeti (1923-2006) was originally composed as a stand-alone piece, intended as a statement of love for a cellist and fellow student at the Budapest Music Academy. Apparently these feelings were never shared, so a few years later Ligeti added a second divergent movement to form a sonata. Dialogo was written as a love-duet between a man and a woman holding a conversation with the lower bass notes sounding tentative and pleading, and the upper register notes responding accordingly. Eventually the two voices mingle simultaneously and the piece comes to an unresolved end. John-Henry Crawford's expressive account brings out the sadness in the lower bass notes, and the cold aloofness of the upper notes to great effect. For those of you unfamiliar with the music of György Ligeti, his reputation rose rapidly when some of his music was used during some of the iconic scenes in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey.

And saving the best for last, the Cello Sonata in D minor, Op. 40 by Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) was composed around the same time as his fearsome Symphony No. 4, a period during his life when the apprehension of being dragged away by the Soviet regime's secret police must have weighed constantly on his mind. And in typical Shostakovich fashion, the musical narrative itself is infected, intentionally or not, by this inceptive phobia. At the onset it sounds very much like something Rachmaninov would have written, especially when the hyper-lyrical main subject appears around the 1:40 mark (unusually beautiful and tender for Shostakovich). But it doesn't take long before the bogeyman of fear rears its ugly head. This beautiful and tender passage, which returns a few times during the first movement, is always quickly shadowed by a repeated three-note motif in the piano's lower register, that could be interpreted as an urgent knock at the door. As a matter of fact, near the end, that knock is replaced by yet another piano passage that sounds like someone creeping up the stairs. Eventually the movement ends shrouded in mystery. Now, as if Shostakovich had been taken away in the night, the second movement sounds like a steam locomotive bound for Siberia. The aptly dark and morose Largo that follows intensifies the sense of bleak and utter desolation that this composer could project like no one else. And again in typical Shostakovich about-face character, the final movement comes in like a court jester, juggling various folk tunes in a slapstick manner, meant to erase all signs of the preceding nightmare.

In other words a powerful 20th century musical statement from the Soviet era loaded with extra-musical innuendos, and emotive and expressive gestures that only good musicians like John-Henry Crawford and Victor Santiago Asuncion can decipher.

Jean-Yves Duperron - June 2021