ESSENTIAL RECORDINGS

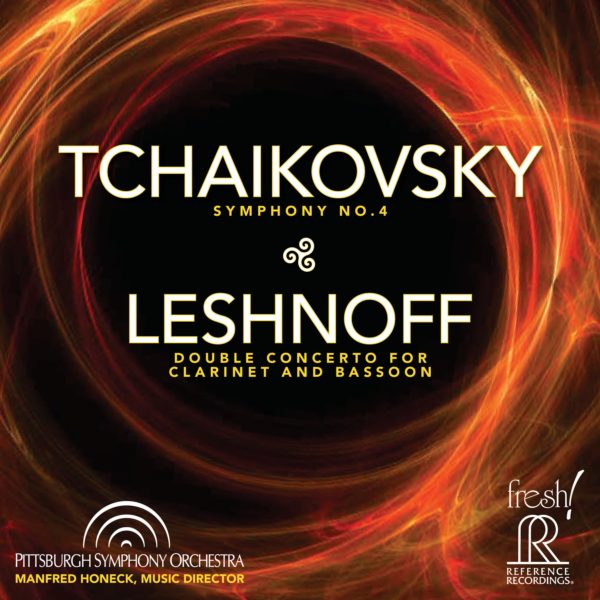

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Opus 36 Jonathan Leshnoff: Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon

May 7th of this year (2020) marked the 180th anniversary of the birth of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), so what better way to celebrate this event than by releasing a brand new recording of one of his most inspired and powerful works, the Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Opus 36. No other composer as ever infused such a high level of anticipatory, emotion-charged dramatics within a score, and in this symphony Tchaikovsky cranked this up to 11. It combines the pathos of Swan Lake and the stoic nature of the Slavonic March, both of which were written the previous year. And as conductor Manfred Honeck points out in the booklet notes, the year 1877 when Tchaikovsky was hard at work on this symphony, was a year of crisis: "This Symphony is about darkness and suffering, but also hope and light. At once, it is on the edge of despair- depressed, hopeless, broken, melancholic and gloomy; but there is also an incredible counterpoint- courageous, self-confident, joyful, optimistic, wild and blissful."

Quite a few symphonies open with a bold, fearless and extroverted statement (Brahms No. 1, Beethoven No. 5, Mahler No. 5, ... to name a few), but nothing quite matches the intensity or impact of the onslaught of brass that Tchaikovsky unleashes right from the onset of the first movement. And the brass ensemble players of the Pittsburgh Symphony certainly give this opening declamation all the weight and power it calls for. It's a rather prolonged movement at over 18 minutes, but Honeck well defines the conflicting thematic aspects of the music throughout, and keeps the tension moving forward, and lends great emphasis mid-movement at the return of the brass statement from the start, and the ensuing battle for supremacy. The final minute or so is so dramatic that you can almost visualize the curtain fall.

As in his famous ballets, Tchaikovsky's affinity for irresistible melodies comes to the fore in this symphony's slow movement, and conductor Honeck and the musicians of the orchestra well project it's idyllic charm. And as far as thrills are concerned, nothing quite matches this symphony's final movement. With a momentum more manic than the 1812 Overture it requires virtuosic playing from all the members of the orchestra, especially the brass section. And again the Pittsburgh brass players nail it. And at the 5:37 mark, when the brass declamation from the start returns, it's punchy enough to push you backwards. And wow, does this orchestra ever show its mettle during the exhilarating race to the finish. Play it loud and feel the orchestral sizzle. Seriously, if you play this in your car, you'll be bouncing up and down the road.

The work that follows, the Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon by American composer Jonathan Leshnoff, heard here for the first time on a recording, is a clever and ear-catching three movement work full of intricate repartee between the two instruments, here played superlatively by Nancy Goeres and Michael Rusinek, the two principal bassoon and clarinet players of the Pittsburgh Symphony. It makes for a pleasant adrenalin-reducing measure following the Tchaikovsky roller-coaster ride.

Jean-Yves Duperron - May 2020