ESSENTIAL RECORDINGS

If you happened to turn on the radio as the first movement of the Symphony No. 1, Op. 10 (Dedicated to the Red Army) by Mieczyslaw

Weinberg (1919-1996) was playing, you would not be amiss in thinking that this must be a work by Dmitri Shostakovich that you had not heard before.

The similarities between the two composers, after all they did become friends, are quite telling. Not so much in the musical language they used to express themselves,

but more so in the similar techniques they used to deliver their message. For example, the layered strings, the lone flute carrying the tune aloft over the orchestra, the

effective use of military sounding percussion, the inclusion of a solo clarinet passage to stress the ridicule, the sharp and repetitive chords to stress a point, etc ... the

list of influences is quite long. They had both suffered through and endured great losses during their lives, and that was deeply reflected in their writing. There is one

trait that sets them apart though. Shostakovich had a tendency at times to be thematically myopic and focus all of the attention on only one subject at a time, until it

developed into something else and moved on. Weinberg on the other hand was more adept at juggling several ideas at once and having them work together towards the

same end. That is immediately obvious in the contrapuntal development of the first movement of this symphony. The Lento movement that follows again

displays a talent for layering different lines to create a light and shadows atmosphere. The final two movements are both driven by strong rhythms and a solid momentum,

that delivers a very effective ending to the whole work.

What an odd, bleak and lonely effect the solo harpsichord exudes as it opens the first movement of the Symphony No. 7, Op. 81 for harpsichord and

string orchestra, a work dedicated to Rudolf Barshai. The strings quickly take their cue from the harpsichord's entry and move on to produce very haunting and evocative

lines within this opening Adagio. The harpsichord does not play very often in this symphony, so when it does the effect is even more gripping. Most of the

time it acts as an extra texture within the fabric of the strings, but when it re-appears solo and repeats the melancholy melody from the introduction, it leaves an

impression. The whole work goes through many changes and conflicts along the way, all the more reason for the unexpected ending to leave a smile on your face.

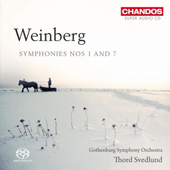

This impressive Chandos recording is the fifth in a groundbreaking series by the label of the orchestral works of Mieczyslaw Weinberg. The first three

volumes are very fine recordings of more of his symphonies conducted by Gabriel Chmura (listed on this site as Essential Recordings). The fourth in the series, conducted

by Thord Svedlund with the same orchestra as this new release, is a superlative account of various Concertos by this composer, and is reviewed on

this site as a Definitive Recording. This series of recordings just seems to become better and better at every step, and this new addition just released in May 2010 is a case

in point.

Jean-Yves Duperron