ESSENTIAL RECORDINGS

I've always perceived the Symphony No. 9 in D minor by Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) as the musical equivalent or counterpart to Dante's Divine Comedy. In the sense that to me, its three movements are tone paintings that represent Hell, Purgatory and Heaven, or an ascending quest for divinity. After all, this monumental symphony is the end result of a lifetime's pursuit of perfection. Or, since I believe that Bruckner suffered from a form of Asperger's Syndrome, could it simply be that with No. 9, after all the revisions upon revisions of his life's work, he finely attained symmetrical nirvana. But enough of my rambling. The detailed and erudite booklet notes, written by conductor Manfred Honeck himself, shed a much more insightful light on Bruckner and his music.

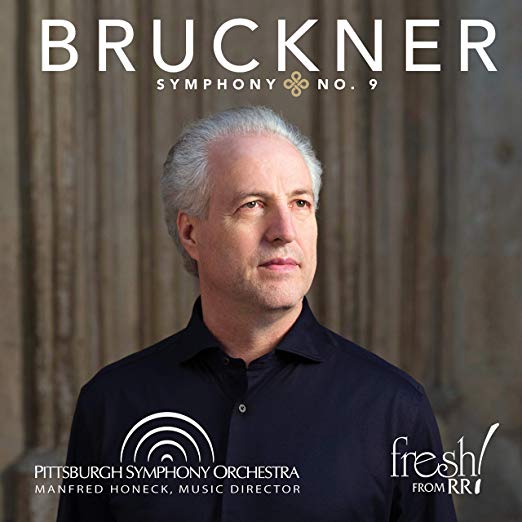

As if a call from the beyond, the magnificent horns of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra infuse a profound sense of eerie and yet powerful stillness within the opening pages. Honeck's slight quickening of the tempo leading to the first appearance of the cataclysmic octaves is well judged and sidesteps the desultory bloating of the orchestra. The string passage that ensues also benefits from a nimble and yet deeply expressive momentum. And throughout the whole first movement Honeck's tight control over the dynamics, and especially the very soft passages, is quite striking. Notice the ever so gradual swelling of the dynamics from the 22:34 point up to the end. A remarkable passage in which Bruckner pushes the harmonic envelope. Again, Manfred Honeck sets a swift pace for the Scherzo with a timing of 10:20 compared to the 12:14 set down by Leonard Bernstein in his 1990 Vienna Phil live recording. And when set against the live Celibidache account which sounds like a dance for hippos, it's a different atmosphere altogether. Surprisingly, the final movement here is almost a full minute longer than the aforementioned Bernstein, clocking in at a solemn time of 27:46. But in this movement, like in the fable of the hare and the turtle, "slow" wins the race. Like a fervent prayer to God, Bruckner's attempt at the sublime should not be rushed. Like all the other composers who died after completing an unusually far-reaching ninth symphony, this movement alone holds something mystifying within its pages. Near the very end, when Bruckner deconstructs the massive chords from the beginning and turns them inside out and upside down (highly unusual for Bruckner), sort of like a massive musical convulsion, had he envisioned his own death? And is the serene beauty of the measures that follow a glimpse at the hereafter? In any case this account is highly gripping. And notice how Honeck's focus on the strings doesn't relent, even when the heavy brass chords are trying to extinguish the music itself.

Unlike the symphonies of Mahler or Shostakovich for example, in which so many passages convey a myriad of possible imagery or emotions, and at which conductors can come from so many different interpretive perspectives, a Bruckner symphony is "absolute" music. You can't evince a different outcome from a harmonic progression or a sequence of chords. It's sound and proportions have to be just right. I would have to say that this "live" performance achieves exactly that.

Jean-Yves Duperron - August 2019